|

Town of Banff surrounded by the

following peaks.....Tunnel Mountain, Mount Rundle, Sulphur Mountain,

Mount Norquay, and Cascade Mountain. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lake Louise in the morning

with Full Moon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Morraine Lake |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peyto Lake |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Climbing the Parker Ridge Trail

(James) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On the Parker Ridge Trail |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Parker Ridge Trail with view of

Sashachewan Glacier |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Video: View of Saskachewan Glacier from Parker Ridge

Summit.

Video: View of Saskachewan Glacier from Parker Ridge

Summit. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Town of Jasper |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stutfield Glacier From Icefields

Parkway |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Boundary, Athabasca, Dome Glaciers,

and Glacial stream viewed from Icefield Parkway |

|

|

|

|

|

|

VIDEO of Wilcox Pass summit with view of Iceland Parkway,

Boundary, Athabasca, and Dome Glaciers

VIDEO of Wilcox Pass summit with view of Iceland Parkway,

Boundary, Athabasca, and Dome Glaciers |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Boundary and Athabasca Glaciers

from summit of Wilcox pass Trail |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emerald Lake with Mount Wapta in

Background, Yoho National Park, British Columbia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emerald Lake, Yoho National Park,

British Columbia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emerald Lake, Yoho National Park,

British Columbia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Burgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is one of the

most famous and important Fossil Sites in the world.

Located in Yoho National Park,

British Columbia on a ridge nestled between Mount Wapta and Mount

Field, lies the Burgess Shale. Discovered by Charles Walcott

in 1909, the Fossils of the Burgess Shale represent an astonishing

snapshot of life during the Late Cambrian period (510 million

years ago). This period followed one of the most spectacular

evolutionary events in the history of life – The Cambrian

Explosion. Within ten million years, a very short period geologically,

a host of hard-body and soft-body complex animals with a variety

of body forms appeared in the fossil record for the very first

time. Nothing like it was seen previously. These creatures represent

the first truly complex animals in the Fossil record. Many of

the modern animal Phyla are represented in the fauna of the Burgess

Shale although several Burgess Shale animals have no counterpart

in modern times and likely were dead end evolutionary experiments.

Half a billion years ago, the world

was a different place: Days were 21 hours long, years lasted

420 days, and the landmasses were clumped together and devoid

of both plants and animals. However, there was abundant life

in the seas. The Burgess Shale quarries are famous not just for

the sheer number and variety of fossils and their rare and lovely

preservation, but also for the window they open to the past.

Multicellular life evolved on Earth about 570 million years ago

with a bang known as the Cambrian Explosion. During a mere 10

million year stretch (a blink of the eye in terms of geologic

time) essentially all the body plans of modern animals alive

today came to be in what was a remarkable evolutionary crescendo

. No fundamental animalian body types have been added since that

time. Even our own remote evolutionary ancesters, the phylum

Chordata (having a backbone and bilaterality), were present in

the Burgess Shale fauna.

The Burgess Shale is special for

another reason. For an intact 500-million-year-old soft-bodied

fossil to endure is extremely rare. To be immortalized as a fossil,

an organism must avoid predation, scavengers and decomposition

and be preserved in an ideal environment, often through rapid

burial. Then the rock stratum containing the fossil must remain

pristine for millions of years, avoiding metamorphosis, compression,

distortion and extreme heating. Finally, if the fossil is to

be studied, it must be unearthed through erosion and, of course,

discovered. Most of the Burgess Shale animals lived on the seafloor.

During the Middle Cambrian, the Burgess Shale quarries lay underwater

just north of the equator, at the foot of a submerged limestone

wall known as the Cathedral Escarpment. Scientists speculate

that ocean currents continuously swept siliceous muds and sediments

over the rim of the Cathedral Escarpment, where they piled in

a wedge at the base of the cliffs. Occasionally, this wedge would

slump downslope, quickly burying any creatures living on the

seafloor at the base of the cliffs. Subsequent preservation of

the Burgess Shale fossils required something of a perfect fossilization

storm, one that only occurred in a very narrow zone. The famous

quarry of fossil-rich shale is about 3 meters high and less than

a city block long, bookended by metamorphically baked shale that

contains no fossils. Proximity to the durable Cathedral Escarpment

— remnants of which can still be seen above the quarry —

is likely what saved the fossils from compaction or warping as

the Canadian Rockies were uplifted during the Mesozoic.

Information from https://burgess-shale.rom.on.ca/

My son and I came across this plaque

while hiking around Emerald Lake during our last day in Canada.

Although I've read books about the Burgess Shale I had no idea

we were in its vicinity.

My son and I came across this plaque

while hiking around Emerald Lake during our last day in Canada.

Although I've read books about the Burgess Shale I had no idea

we were in its vicinity. |

|

|

|

|

|

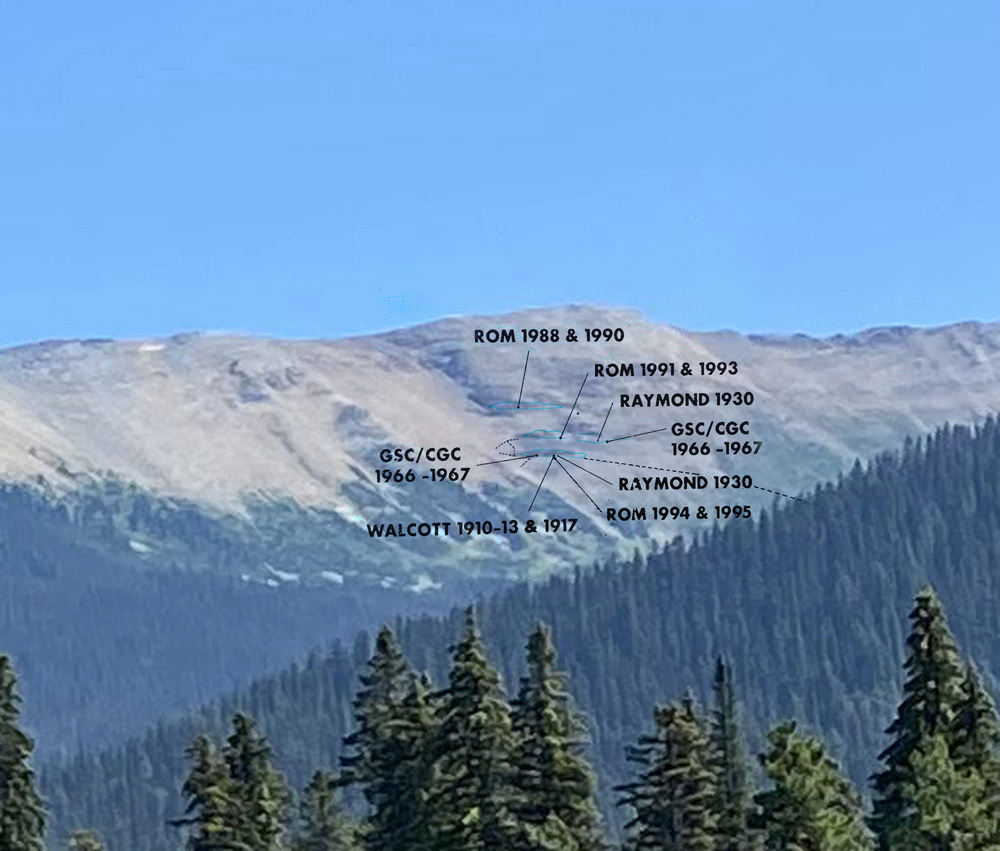

Site of "Burgess Shale"

nestled between Mount Wapta and Mount Field

Yoho National Park, British Columbia

(my photo) |

|

|

|

|

|

Close up of the Burgess Shale Quarries

(my Photo)

Historical Quarries:

Charles Walcott: Original discoverer

of the Burgess Shale

Geological Survey of Canada - Commission

Géologique du Canada

Percy Raymond, Curator of Paleontology

at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology

Royal Ontario Museum

Books on the Burgess Shale

Wonderful Life, The Burgess Shale

and the Nature of History, Stephen Gould, 1989, W.W. Norton.

The Fossils of the Burgess Shale,

Derek Briggs, Douglas Erwin, Frederick Collier and Chip Clark,

1995, Smithsonian Institution Press.

The Crucible of Creation: The Burgess

Shale and the Rise of Animals, Simon Conway-Morris, 1999, Oxford

University Press

Web Sites about the Burgess

Shale

https://burgess-shale.rom.on.ca/ |

|

|

|

|

|

|